Building Your Repertoire with Transcription

I once heard from a professor that in order to improve as a musician, there are three pillars that need to be addressed: transcription, practice, and playing with people. Up until now, I have spent a lot of time thinking and talking about practicing in my videos and private lessons, so let’s take a day off from that. Regularly getting together with real people to play, if I’m being honest, is something of a weak point for me. It is something I am working on though, so we’ll save that topic for another day when I have more to say. That leaves us with the topic of transcription and, by extension, learning repertoire. So let’s talk about the best way to go about this process, and just as importantly, the reason for doing it.

Part 1: Purpose

Before breaking down the process and the method for transcribing music, I want to talk about how transcription helps us; and I want to start by posing a question for your consideration: how many albums do you know so well that you can sing along to every song on it, front to back? If you think there are a few, I challenge you to be specific and name them. If you are able to honestly name a few, then you’re doing better than most! But before you start feeling too good about yourself, I’ll add one more component to this question for the musicians out there: are you currently satisfied with your musical ability and sound? If you wish your sound was different, do your listed albums represent the musical direction you want to move toward or are they relics of past musical aspirations and interests?

This question was posed to me about fifteen years ago while at university, albeit, in a bit more of an “old-man yells at clouds” kind of way: “Kids these days have unlimited access to the world’s entire music catalogue but they don’t know any of it. Even the music they claim to love, they don’t know. How many of you [students] can actually sing along with your favourite songs and solos?” And while the question was posed with a slightly bitter and frustrated tone, the message stuck with me: if you want your sound to be anything like your favourite artists, you have to know their music, and I mean really know it.

One way I like to approach this idea of really knowing a piece of music is by comparing listening to nutrition. Imagine that every song or album has a nutritional value: pop music is beautifully manufactured, sugary, sweet candy that gives us quick dopamine hits; metal music is heavy and dense like a hearty steak, full of protein and iron while completely lacking in other vital nutrients; and jazz is like a vitamin-infused kale smoothie – you know it’s supposed to be good for you, but calling it an “acquired taste” feels too generous. Now, every time you “consume” a piece of music, you break it down at a subconscious level, through your “creative digestive system,” until you ultimately absorb it into your artistic make-up. Some music lacks nutritional value and can be absorbed quite quickly - with just one or two listens - whereas other music will continue to offer nutrition throughout a lifetime of repeated listening. Usually though, after enough listening and digestion, there will be nothing left to extract and you can say that you have fully absorbed it into your creative voice.

This digestion and internalization process is at the core of why we transcribe. It allows us to develop our own musical sound while learning the language of a genre. In idiomatic terms, we become what we eat, or in this case, we sound like what we listen to.

Nostalgia is a hell-of-a drug.

Photo: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/10/opinion/sunday/favorite-songs.html

In theory, this all sounds fine and well: let’s just listen to more music with deeper focus and we’ll all become better artists. But there are a couple of issues that get in the way and make this more complicated than it should be.

First, at the individual level, people commonly stop seeking out new music as they get older. This usually happens around the age of thirty (which now puts me squarely in the “at-risk” category), well after our musical preferences have been formed during our hormone-driven teenagers and young-adult years. This loss of musical curiosity often coincides with a more stable phase of life - when people no longer feel the need to search for meaning or identity through art. For the average person, this isn’t a big deal - people can find joy and purpose in many other things - but for an artist, it’s significant: without new or focused inputs, development and creativity stagnate. All of our ideas (or lack thereof) end up originating from from the same sources of music that we digested and absorbed long ago.

Second, there is a problem at the societal level: because of the overwhelming quantity of music available to us, it is harder than ever to focus on the music that we love. Streaming services give us access to virtually every song and album ever created and it can feel impossible to not bounce around, trying to listen to it all (like making sure you get all the free samples at Costco). With all of this choice, a sense of FOMO (fear of missing out) naturally kicks in. We worry that if we are listening to one thing, we are missing out on all the songs that could be better.

I’ve often found myself in a loop - listening to thirty-second snippets of every song that I come across, trying to ensure that I’m spending time on only the “best” quality music, while ironically not spending any real time on anything. Combine this streaming service effect with the influence of social media and fast-consumerism and we end up in a culture where music is often just used as a tool to retain our attention spans for just a few moments - just long enough for someone to sell us a product or rack up a view count - rather than something to which we give our full attention, for extended periods of time.

The days where an artist was a clear amalgam of the twenty or so records they listened to on repeat - until the grooves wore out - are no longer our reality (am I becoming the old man yelling at the clouds?).

Abe Simpson, yelling at the clouds (S13, E13)

So, how do we fight the artistic stagnation that is caused both by getting older and from living in a late-stage capitalist society?

Listen. Sing. Learn.

Listen to the music you want to digest, and listen to it a lot. Listen to it over and over again, like a teenager trying to make sense of the world through the sounds of a fringe punk band that only they know about in their small, suburban town. Sing along with it with a fervour that would spark full, red-faced embarrassment if you were caught. And finally, learn it on your instrument, translating its language to an expressive medium from which you can voice your own creative impulses.

Make no mistake, this process takes work. But while we may not be driven by the same emotional forces we once were, we can pursue this endeavour with the wisdom and awareness that we are in this for the long run. I’d wager that if you are still playing an instrument at thirty years of age - or older - then you have already decided that music is central to your well-being. And a part of that well-being, at least for me, includes the ability to continually improve and grow, so that we may give voice to the sounds that are inside our heads.

Pursuing this is reason enough to keep feasting on the sound waves.

Canadian jazz-guitarist Ed Bickert. What a life full of music can be. Photo: cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/remembering-canadian-jazz-great-ed-bickert-1.5111657

Part 2: Method

With the general purpose of transcription established, let’s now talk a little more tangibly about how best to learn new music and build out your repertoire.

By far, the most beneficial way to learn is by ear; after that, learning from musical notation still provides many benefits; and finally, learning from TAB will contribute the least to your overall musical development. Just to manage expectations, these methods are not only ordered from most effective to least - but also from hardest to easiest. But since we are here to talk about the best way to learn, we won’t shy away from the challenge. In fact, my goal is to break it down so that no single element of it will feel overwhelming and you’ll be confident starting to transcribe on your own.

So here it is, how to learn by ear.

Step 0: Have a Reason to Learn

While it is the hardest way, learning a song or solo by ear offers far more benefits than simply reading fret numbers from a TAB:

You’ll develop your general musical memory and will retain the specifics of the song for longer.

You’ll discover new ways to play your instrument - especially if you’re learning something written for - or played on - another instrument.

You’ll improve your ear training, allowing you to transcribe faster and tackle more complex material.

You’ll form a personal connection and sense of ownership over the piece, techniques, and concepts you’ve learned.

You’ll more deeply absorb the sonic ideas into your own musical voice.

Despite the clear and many benefits, it can be hard to commit to the effort if you don’t have a convincing reason to begin with. Having a tangible goal is essential to staying motivated and making it to the end. Some examples of goals include:

Wanting to be able to play a tune at a jam session or performance

Playing it for a teacher

To discover new compositional techniques or concepts.

Expanding your solo or improvisational vocabulary.

Whatever your reason is, make sure that you can clearly articulate it before you begin. Also, recall it on occasion, when the transcribing gets tough.

Step 1: Listen & Sing (Yes, even if your voice is terrible)

To have your piece enter your long-term memory, you need to internalize it to the point that you can sing along with it. This means listening to it dozens - or even hundreds - of times.

The first time you try this, it may start to feel pointless around the twentieth listen. You’ll start to feel like you have it “good enough” and be tempted to move onto the next steps. But unless you can sing the entire thing - hitting all of the rhythmic entrances and following the melodic contours - you need to keep listening. I’ve learned from experience that spending enough time in this step is essential to the success of what comes next. If you do it this way, you’ll never go back to figuring out a song one note at a time - and you’ll wonder how you ever survived one minute of that torturous task.

Once you’ve listened to it ad nauseam, you can test if you know the piece by singing the song. First, sing along with the audio track, then try without it. If you’re able to “hold the tune” and have it be recognizable rhythmically and melodically, then you probably have a solid grasp of it and are ready to move on to Step 2.

Professional musicians who have developed their ears with this process will often fully learn songs this way, sometimes, even doing it on the plane on their way to the gig where they will be performing it.

I want to make one last point about singing: many people who do not regularly sing are very self-conscious about their voices (I know I was when my first public vocal performance was singing scales in front of my ear training class). As someone who used to not be able to match a pitch with their voice, I promise, your voice will get better if you begin using it more. Like anything else, if you don’t work on it, it won’t improve.

The good news though, is that if you’ve never worked on singing, then even a little bit of effort here will yield drastic results. But if you’re still uncomfortable singing out loud, that’s okay. Another option is to whistle. The main reason we sing during the transcription process is to demonstrate audiation – your ability to memorize sounds, hear them internally, and reproduce them. Whistling is just another way to produce a pitch, so technically, it serves the same function.

Still, I recommend taking the time to develop your voice at least a little. The effort is absolutely worth it in the long run.

Larnell Lewis, drummer and educator.

Photo: https://www.socanmagazine.ca/features/the-increasing-mindfulness-of-larnell-lewis/

Step 2: Learn It on Your Instrument

This step is probably the most straightforward: take the music that you can now sing and find the notes on your instrument. Try to do this from memory, but don’t hesitate to use the audio track whenever you need to re-center yourself to the harmony or check specific notes you’re unsure of. You likely won’t have all of the notes perfectly mapped in your head from Step 1, so keep using the audio track as needed.

Though, pay attention to how often you’re using the audio. If you’re still heavily reliant on the recording and find yourself replaying two-second snippets over and over again to catch one note, then spend a little more time just listening, in Step 1.

As you’re learning the notes on your instrument, consider the technical aspects of the passages and figure out the most effective to play them. On the guitar especially, there are many different ways to play the same notes, so really pay close attention to the phrasing and which strings and fingerings are being used.

If what you are transcribing is not played on guitar, experiment with several fingerings to find which ones feel and sound the best. Doing this will help you develop your own personal sense of technique and phrasing and can even lead you to discovering new ways of thinking about your instrument.

Step 3: Practice & Internalize

Once you’ve learned how to play the notes, it’s time to make the music flow by practicing it along with the original recording. If you can’t yet play it up to speed , slow it down using one of the many software tools available (I have been using the Amazing Slow Downer for over fifteen years, but most DAWs can accomplish the same thing). There’s no reason not to slow something down - other than the ego. Playing something at a slower tempo is a natural part of any learning process, so give yourself the best possible conditions to improve.

While playing along at your chosen tempo, focus on matching the rhythmic feel and dynamics of the performance. This helps you to absorb the touch and nuance of the player you’re transcribing. Then, gradually work it up to full tempo while doing your best to replicate the tone and feeling of the piece.

If the song is far faster than your current physical playing ability, you have a few options:

Use it as a technical exercise to work on improving your speed.

Learn it up to a comfortable tempo and leave it there.

Reconsider the difficulty of the transcription, and next time, choose something more aligned with your current technical level.

Try to be realistic about your ability level and which pieces of music will teach you the most with where you are at. If you’re unsure about what pieces of music will help you grow the most, then it is a good time to seek the feedback of a teacher.

Once you have the song up to your target tempo, I recommend doing the following before moving on from the piece:

Record yourself playing it with only a metronome backing you. Listen back and see if you successfully reproduced the rhythmic feeling and the dynamics, in addition to all the correct notes.

Insert your favourite passages into different musical contexts. This means transposing them to different keys, moving them to different areas of your instrument, changing their rhythmic structures, using them in different genre contexts, or playing them at different tempos. This step is especially important for anyone looking to expand their solo vocabulary or learn genre-specific language.

Improvise (or “noodle”) while incorporating as much of the transcribed material as possible. Do the lines feel like they’re part of your natural voice, or do they still sound imitative? The goal is for the transcribed material to blend seamlessly into your existing playing.

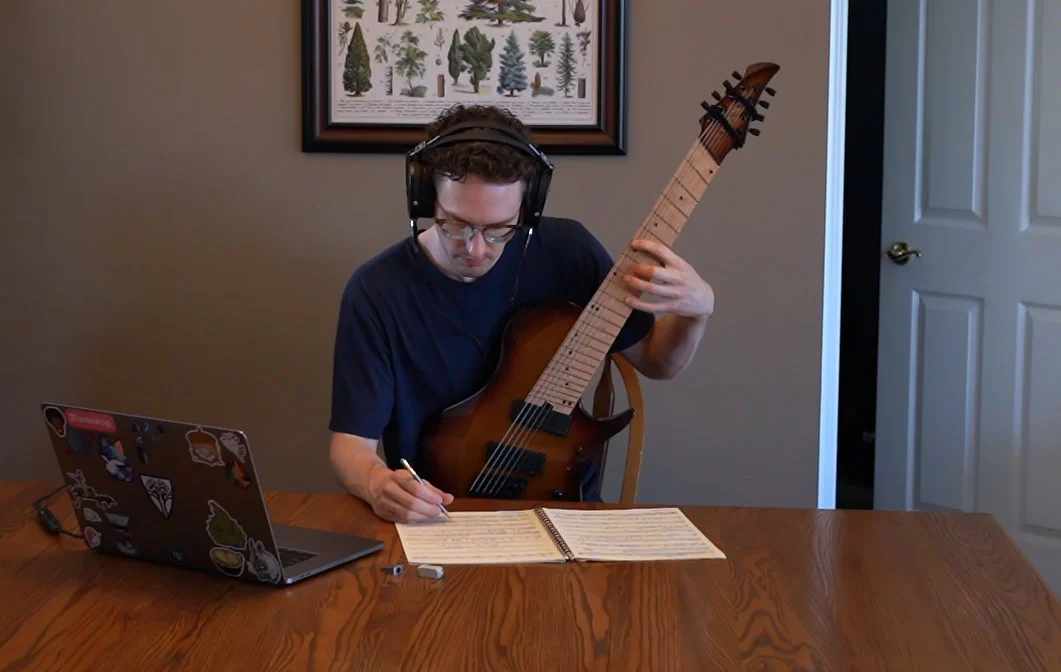

A few transcriptions from my time in school.

Step 4 (Optional): Write It Out

People who haven’t learned this method of transcribing often begin the process by writing down the notes before they’ve adequately listened to the song. They go one note at a time, notating it as sheet music or TAB, with the intention of learning it from the page later.

I admit, I have done this quite a few times, especially when I first started transcribing as a teenager. Even though it was tedious and painful, I believed it would be beneficial for me because it would help me learn how to hear pitches and rhythms. What I didn’t know though, was that there are far more effective ways to practice pitch recognition. Transcribing an entire piece, note-by-note, before learning it by ear, ends up being a long-winded and arduous way to learn it from sheet music - and it bypasses the main benefits that transcribing offers.

Imagine a first-grade student trying to learn calculus; sure, it sounds impressive and with enough time and help, they might even be able to grasp parts of it. But if the goal is to develop a functional understanding of math in the long term, their time would be better spent working on material that is appropriately tailored to their level of comprehension.

So, if you find that learning a song so difficult the only way to learn it is by writing down every note as you go, then it’s a clear sign that you need to start with something easier – some basic exercises or a simpler song.

While that is how not to approach notating a transcription, there are still valid reasons to notate your work, so long as you do it after you’ve learned it by ear and can play it. Some good reasons for notating include:

Theoretical analysis (harmonic, scalar, rhythmic, phrasing, compositional, etc.)

Further language absorption work (we won’t get into it here but you can be read about here if you’re interested)

Creating a deliverable (like for a school assignment, or for a student)

To improve your notation skills

There may be more reasons to discover, but I’ll just leave you with one final reminder: please make sure you’re not writing it down one note at a time before you can sing and play it, for your own sanity and well-being.

David Liebman, jazz saxophonist and educator.

Photo: https://www.dacapo-records.dk/en/artists/david-liebman

And that’s it! If you go through these steps, you will have a piece of music deeply digesting, ready to emerge in unexpected ways as you continue to develop your artistic voice. Along the way, you’ll also improve your ability to identify pitches, rhythms, and harmonies, and further develop your understanding of your instrument.

This process can sound almost magical, but I don’t want to leave you with any illusions that it is quick or easy. While musicians use their ears to figure out new music all the time, most only complete a handful of transcriptions in their lifetimes to this depth and thoroughness.

So, the next time you are feeling stuck in a developmental rut and are looking for ways to improve, ask yourself: Is transcription what I need most right now? Maybe instead, one of the other pillars needs more attention. Perhaps your practice schedule has become inconsistent and sporadic, or maybe you haven’t played music with another human being in two years and you need to rebuild that sense of real-time musical reflexiveness. Transcription is a wonderful tool and has many benefits, but it is not the only one out there that can help you improve.

On that note, if you are looking to improve at the guitar and don’t know what you should be working on, it may be time to meet with a teacher. I offer private lessons as well as custom practice packages for those who don’t have the time for regular lessons. I would love to hear from you and help you along in your musical journey, so don’t hesitate to reach out.